Storie da Zaatari – News from Zaatari

-

0

-

0Shares

[english below]

Ancora una volta la nostra amica Anna Maria Bruni ci invia delle storie raccolte in prima persone nei campi profughi siriani. E lo fa con la consueta sensibilità / Once again, our friend Anna Maria Bruni - photographer and activist - sends us news and stories from Syrian Refugee Camps. And she does it with her usual touch.

Dalla Siria senza speranze

All’ingresso dell’area destinata al controllo dei permessi ho incrociato tre uomini siriani. Erano appoggiati al muro e aspettavano la loro registrazione al campo. Sembravano tre cloni, tanto erano simili tra loro per l’aspetto, e anche il loro sguardo era in qualche modo clonato. Tutti e tre con la stessa espressione, un’espressione assente, silenziosa.

Di chi non sa bene come dove e quando. E soprattutto perché.

ph: Anna Maria Bruni/S4C

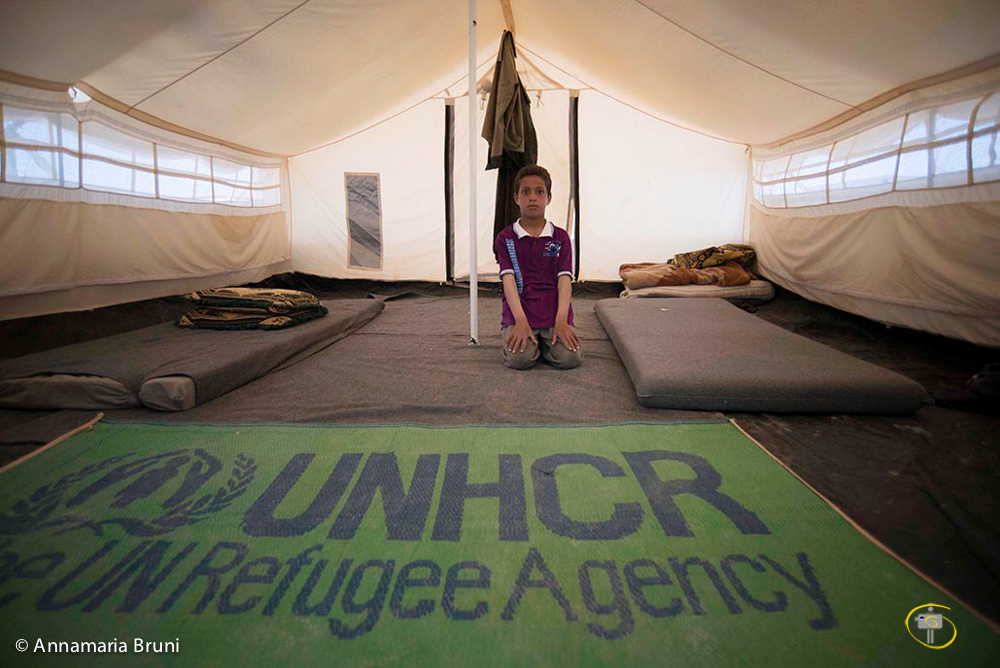

Il sole e la primavera danno al campo profughi di Zaatari un aspetto più umano. Le strade si ripopolano dopo un freddo inverno e la temperatura non è ancora quella torrida dell’estate, che presto arriverà.

La primavera porta speranza, rinascita, e nuove aspettative .

Anche per i profughi siriani massacrati da tre anni di guerra.

Zaatari si trova a 10 Km dalla città di Masfraq, in Giordania, proprio vicino al confine siriano. L’UNHCR parla di 106 mila persone ospitate dentro il campo, diviso in dodici distretti, con scuole, ospedali, centri per donne, centri distribuzione cibo. Aree gioco. Negozietti.

La via principale, quella di entrata, l’hanno chiamata la Champs-Elysées, perché prende il nome dall’ospedale francese vicino, uno dei primi ad essere operativo. Una via lunghissima dove si può trovare qualsiasi cosa, frutta, verdura, profumi, abiti da sposa in affitto.

Dall’inizio della rivoluzione siriana, avvenuta nel marzo del 2011, l’esodo è stato lento ma costante. L’afflusso di siriani in fuga continua quindi a riversarsi prevalentemente sugli stati contigui, i quali, volenti o nolenti, mantengono aperte le proprie frontiere. Libano, Giordania, Turchia e, in misura minore, Iraq ed Egitto.

Due milioni di profughi nel giro di tre anni. Un paese devastato come i suoi abitanti. Una guerra che non accenna a finire, inquinata da cellule terroristiche di diversa provenienza, da guerre religiose che poco hanno a che fare con quella rivoluzione popolare che chiedeva solo riforme e maggior dignità. Stroncata sul nascere da una repressione feroce da parte del regime.

Quello che i siriani oggi sanno è che non si può più aspettare la fine della guerra.

Chi ha resistito dentro il paese fino ad adesso l’ha fatto perché nutriva questa vana illusione. Oggi invece sempre più rifugiati sono consapevoli che non ci sarà un termine a breve.

“Non c’è futuro in Siria. In Siria si muore, e basta. Per mano del regime, di estremisti religiosi. Per bombe, armi chimiche, mitragliate o coltellate. Per fame.”

Tutti passano dal campo, per periodi brevi o lunghi, e molti lasciano il campo. La permanenza all’interno dipende dalle possibilità economiche di ciascuna famiglia: quelli che possiedono una piccola somma di denaro riescono ad affittare case nelle città vicine, mentre tutti gli altri sono destinati a rimanerci per lunghi periodi.

Mohamed, ventidue anni, viene da Damasco. e studiava architettura. Suo padre e suo fratello sono stati uccisi da un barile bomba. Quando mi racconta quello che gli è successo non vedo in lui nessuna traccia di disperazione, ma solo una terribile rassegnazione alla vita.

“Non ho soldi, vivo dentro la tenda con mia moglie da nove mesi ormai. Ho smesso di sperare in un futuro in Siria. Per questo vorrei almeno avere i soldi per iniziare una mia attività qui, nel campo. Mi piacerebbe vendere biciclette. Per adesso non posso far altro che sopravvivere, aspettando il mio caravan”

La guerra dei prefabbricati

I “Caravan” non sono altro che i prefabbricati, oggetto conteso da tutti i rifugiati, dal più piccolo al più anziano.

Chiunque si trovi nelle tende si lamenta di non aver il prefabbricato. E’ il primo argomento che affronti quando vai a visitarli. Chi vive nei prefabbricati è un privilegiato. Molti di quelli che sono arrivati due anni fa hanno questa grande fortuna, alcuni ne possiedono due o tre, per la propria famiglia e quella di madri, fratelli e sorelle.

Khaled Soliman è uno di questi.

Venditore di polli arrosto, trentasette anni, Khaled è arrivato a Zaatari nel 2012. E mi dice “ Esattamente l’otto agosto alle quattro e dieci del mattino” perché certe cose non si dimenticano, precisa.

ph: Anna Maria Bruni/S4C

Khaled arriva da Dar’a, una delle città vicine al confine giordano, ed è un fortunato. Per diverse ragioni: è riuscito a portare tutta la sua famiglia nel campo, madre e zia comprese. Possiede un prefabbricato da circa due mesi, dopo otto di tenda. E’ riuscito in un anno a costruirsi un piccolo spazio dove vende polli arrosto e hamburger.

Ha sette figli, e vanno nelle scuole del campo.

Non si può dire che suo cugino Ragab, di trentasette anni, abbia avuto la stessa fortuna.

Lui è arrivato al campo privato di una gamba, un dito, e con un fratello in meno, che come lui combatteva contro il regime nella Free Army, ma sfortunatamente è rimasto ucciso durante un bombardamento.

“Non mi ricordo nemmeno più cosa vuol dire una vita normale. Tre anni possono sembrare una vita se vissuti così. Una gamba in meno è il male minore. Se non l’avessi persa, sarei ancora in Siria, a combattere fino alla fine dei miei giorni.”.

Dall’inizio del conflitto nel 2011 e, soprattutto a partire dal 2012, il flusso di profughi riversatisi nei paesi vicini si è intensificato in quantità e rapidità. Nell’arco di 18 mesi, il numero di siriani in esodo è passato da 40 mila, dato di marzo 2012, a due milioni, contati a settembre 2013. A questi, si aggiungono tutti coloro che ancora attendono di essere registrati e i 4,5 milioni di sfollati interni.

Ogni giorno arrivano al campo tra le 150 e 200 persone, ed è in questo fiume di persone che ieri è arrivata la giovane Amnah.

Seduta in un lettino nel limbo dei nuovi arrivi al campo, aspetta con ansia l’assegnazione di tenda, coperte e tappeti per iniziare la sua nuova vita a Zaatari.

Ha ventuno anni e tiene in braccio una bambina di un paio di mesi. La guarda e mi dice che hanno dovuto aspettare per due giorni al confine siriano, senza acqua né cibo.

“ Ero disperata, non per me, ma per mia figlia. Ho pregato un soldato di darmi un po’ d’acqua almeno per lei e dopo quattro ore l’ha fatta bere dal suo bicchiere.”

Mio marito aveva problemi mentali, e con la guerra si è aggravato. Quando siamo arrivati al confine giordano ha dato un po’ di matto. I soldati giordani per paura gli hanno sparato ad una gamba. Adesso è all’ospedale a Mafraq, spero cahe ci raggiunga presto. Sono così felice di avercela fatta, di essere qui, finalmente al sicuro.”

Le spose invisibili

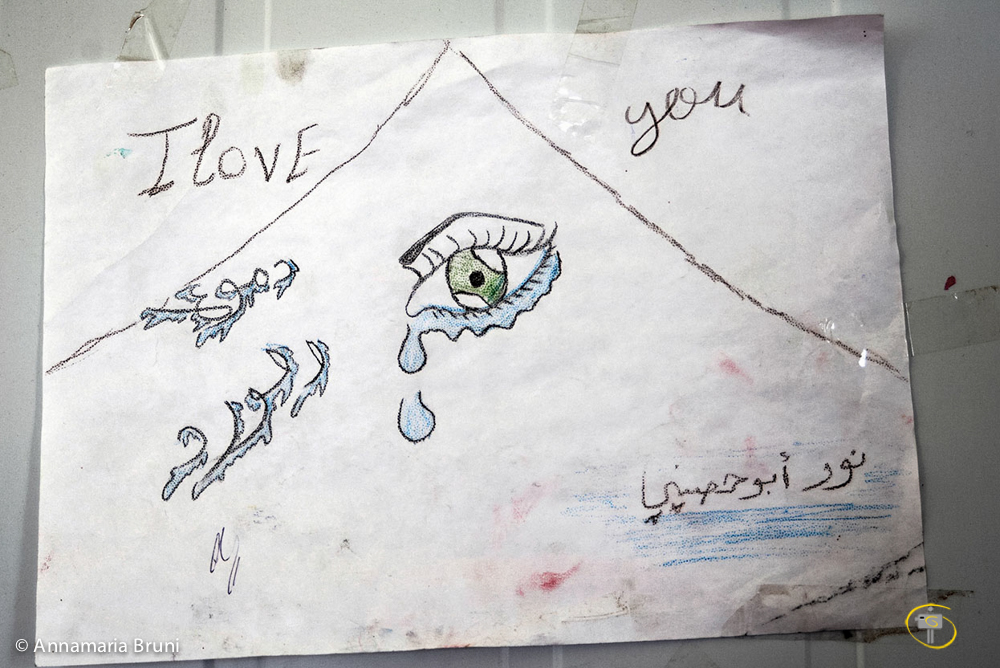

Asmae è una delle 53.000 donne del campo, presenze schive e fondamentali. Le donne nel campo rappresentano più della metà della popolazione. Tante hanno perso il marito, i fratelli, i figli. Molte sono adolescenti in età da matrimonio..

Considerando il fatto che vengono da famiglie disperate, non c’ è da meravigliarsi se esiste un nascosto mercato di spose “invisibili”.

Molti uomini decidono di acquistare la terza o la quarta moglie tra le rifugiate siriane, perché sono belle, giovani. E costano poco. Vendendole le famiglie sperano di assicurargli un futuro migliore, sicuramente lontano dalla guerra, dalla povertà, dalle privazioni e dai disagi del campo.

Queste fanciulle accettano tristemente questo destino e finiscono i loro giorni sotto il volere di qualche benestante arabo troppo annoiato dalle mogli precedenti.

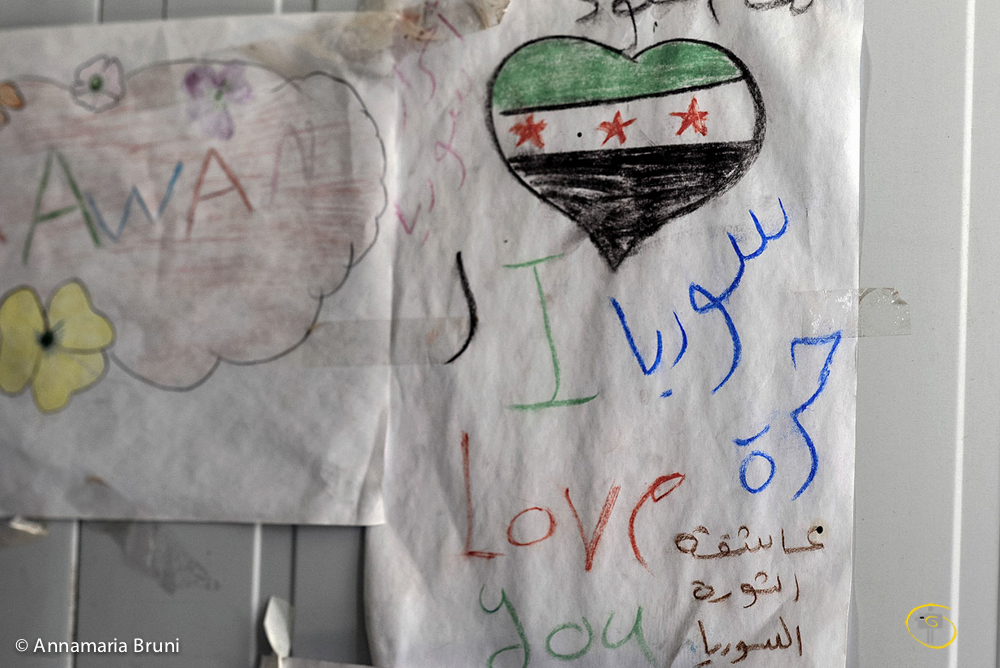

Il 14 marzo scorso si è aperto il quarto anno di un conflitto di cui ancora non si scorge la fine e che sta trascinando con sé conseguenze che si protrarranno per diversi decenni. Oltre 140 mila vittime, più di un milione di bambini affetti da traumi legati al conflitto, un’intera generazione deficitaria in termini di istruzione e assistenza sanitaria, l’economia di un intero paese letteralmente dimezzata in termini di produzione e occupazione e una delle comunità di rifugiati più grandi al mondo che guarda come è diventata la propria terra e non vuole più farvi ritorno.

Facendo diventare Zaatari la quarta città giordana nel giro di pochi anni.

Quello che mi porto dietro della mia visita a Zaatari è confusione, sole accecante, tempeste di sabbia, allegria, rassegnazione, rabbia, ingegno nel sopravvivere.

Quello che mi porto dietro di Zaatari è il cuore dei siriani, persi dentro una guerra infinita.

Anna Maria Bruni/S4C

PS Ringrazio ISPI - Anna Pascale per i dati sui rifugiati

Hopelessness from Syria

(story by Annamaria Bruni / traduzione di Ahmed Hegazi)

I met three Syrian men at the entrance of the area destined for the control permissions. They were leaning against a wall and waited for their registration to the camp. They looked like three clones; so similar to each other in appearance, even their eyes were somehow identical.

All three with the same expression, an expression of absence and silence; of those who are lost, do not quite know ‘how’, ‘where’ and ‘when’.

Above all, they certainly don’t know ‘why’.

The spring sunshine gives a different feel to the Zaatari refugee camp. The streets are recovering after a cold winter and still the temperature is not that hot as it is in the summer time, which is fast approaching. Spring brings hope, rebirth, and new expectations, even for Syrian refugees massacred by three years of war.

Zaatari is located 10km from the city of Masfraq, Jordan, right near the Syrian border. UNHCR has 106,000 people hosted in the camp, which is divided into twelve districts, with schools, hospitals, centres for women, food distribution centres, play areas and shops. The main street at the entrance is called the ‘Champs-Elysées’, named after the French hospital when it became operational.

A long street where you can find anything; fruits, vegetables, perfumes and even wedding dresses for rent. Since the beginning of the Syrian revolution, which took place in March of 2011, the exodus has been slow but steady. The influx of Syrians fleeing their homes therefore continues to pour out, mostly into the states contiguous to the scene of the tragedy, which, haphazardly, keep their borders open. Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and, to a lesser extent, Iraq and Egypt. Two million refugees have fled within the last three years. A torn country and its torn inhabitants. A war that shows no signs of ending, polluted by terrorist cells of different origins, from the religious wars that have nothing to do with the popular revolution that was just asking for reforms and dignity; nipped in the bud by a ferociously repressive regime. What the Syrians know is that they cannot wait until the end of the war.

ph: Anna Maria Bruni/S4C

Those who have resisted and remained in the country until now have done so because they had this vain illusion that it would end quickly. Today, however, more and more refugees are aware that there won’t be a solution in the short-term.

"There is no future in Syria. In Syria you die, and that's it. At the hands of the regime, religious extremists. From bombs, chemical weapons, machine-gunned or stabbed. And finally, from starvation. "

Everyone passes through the camp, for short or long periods, and many leave it immediately. The stay inside depends on the financial/economic situation of each family : those who have a small amount of money are able to rent homes in neighbouring towns, while all the others are destined to remain there for long periods.

Mohamed, 22, is from Damascus. His father and brother were killed by a bomb barrel. When he was telling me what happened to his family, I saw no trace of despair, but a terrible resignation to life.

" I have been living in a tent with my wife for the last 9 months. I've already given up the thought of going back to Syria. Right now, I would like to have my little business here, inside the camp, selling bicycles for example. But what is really important now is to get the caravan as soon as possible."

The ‘war of the prefabricated’.

The "Caravans" are nothing more than the object sought after by all refugees, from the youngest to the oldest. Caravans are referred to as mobile homes. Everyone in tents is complaining about not having a prefabricated. Those who are living in the prefabs are privileged. Many of those who arrived two years ago had this “great fortune”. Khaled Soliman is one of these. A seller of roast chicken, 37, Khaled arrived in Zaatari in 2012. He says:

" On the 8th of August at exactly four- ten in the morning " because certain things can not be forgotten, he points out. Khaled comes from D’aara, a city near the Jordanian border and he’s a lucky one, for several reasons : he was able to bring his entire family into the area, including his mother and aunt. He has a prefab since about two months ago, after eight months spent in a tent. He managed, in one year, to build a small space where he sells roast chicken and burgers. He has seven children and all of them are going to school inside the camp. His cousin Ragab, 37, hasn’t had the same luck. He arrived at the camp having lost a leg, a finger and having lost a brother as he fought against the regime in the Free Army, unfortunately killed during a bombing raid.

"I do not even remember what it means to live a normal life. Three years seems like a lifetime when lived in this way. One less leg is the lesser of two evils. If I had not lost it, I’d be in Syria, fighting to the end of my days ".

Since the conflict began in 2011, and especially since 2012, the flow of refugees pouring into neighbouring countries has intensified in quantity and speed. Within 18 months, the number of Syrians in the exodus has increased from 40,000 in March 2012 to 2,000,000 counted in September 2013. To these we add all those still waiting to be recorded and 4.5 million internally displaced persons. Between 150-200 people are arriving into the camp every day and it is in this river of people that, yesterday, came the young Amnah. Sitting on a cot, in the limbo associated with new arrivals at the camp, eagerly waiting the assignment of tents, blankets and rugs to start her new life in Zaatari. She is 20 and holds a little girl of two months. She looks at me and says that they had to wait for two days at the Syrian border, without food and water.

" I was desperate, not for me but for my daughter. I asked a soldier to give me a bit of water and four hours later he made her drink from his glass. I hope my husband reaches us soon. I am so happy to be here, safe at last ".

The invisible brides.

Asmae is one of the 53,000 women in the camp, a bashful and important presence. They represent more than half of the population. Many have lost their husbands, brothers, sons etc. Many adolescents are of marriageable age. Considering the fact that families are desperate, it is no surprise that an underground, ‘invisible’, market for brides is becoming an issue in the camp. Many men decide to buy their third or fourth wife amongst Syrian refugees because they are beautiful and very young. And, more importantly, they are cheap. By selling them, families are hoping to assure them a better future, far away from war, poverty, deprivation and the hardships of the camp. Most of the time these girls grudgingly accept their fate and end their days under the will of a few wealthy Arabs who have grown bored with their previous wives.

ph: Anna Maria Bruni/S4C

We entered the fourth year of the conflict on the 14th of March that has no end in sight and that is creating consequences that will last for several decades. Over 140,000 victims, more than one million children affected by conflict-related trauma, an entire generation deficit in terms of education and health care, the economy of an entire country literally halved in terms of production and employment, this community of refugees is becoming one of the biggest in the world, watching what has become of their own land and who do not want to return to it anymore. In these years, Zaatari has become the fourth largest city in Jordan. What I bring back from my visit to Zaatari is confusion, blinding sun, sand storms, joy, resignation, anger and ingenuity to survive. What I bring from Zaatari is the heart of the Syrians, lost in an endless war.

-

0

-

0Shares

There are no comments

Add yours